Doing and Not Doing

One:

Just over six weeks ago, it was New Year’s, and my social media feed was filled with earnest exhortations to leave behind what no longer serves you. That list is always pretty accessible to me—perfectionism, avoidance, workaholism, fear of failure, self-doubt, procrastination, family size bags of tortilla chips—but what I didn’t have on my list was my appendix. Nine days into the New Year, the good people at my county hospital took it from me. The general surgeon who was tasked with the job afterward pronounced it “nasty”, before sending off the little wrinkled thing to some lab bench where it was memorialized (rupture!) in a report on My Health Portal.

After surgery, I sat at home, on our farm in rural western Colorado, on days growing increasingly cold, watching as my husband Jay took on my chores with our goats and dogs, and cooked dinner. Suddenly, there was no parity in our relationship: he did things and I didn’t. He was mucking, feeding, grocery shopping, vacuuming. Feebly, I washed our towels, wiped some counters, and went back to bed. I went back to work in limited fashion, to the bookstore I opened three years ago. Somewhere in there, a trip back to the hospital for infection. More rest. It was four weeks before I was permitted to return to my normal life, allowed to lift things that weigh more than ten pounds.

Me, with goats.

Photo: @IzzyLidsky

Two:

Now, it’s been six weeks since the appendectomy. The glue the surgeon used to close me up has finally peeled off, leaving tiny red scars on my belly. It’s Sunday and I am cleaning. Change and wash sheets and towels, dust mop and sweep, clean the kitchen and bath. There is such pleasure in cleaning: the immediate impact of a cloth across a counter, of folding a towel, the odor of vinegar and glass cleaner. It’s work, and in the same way that I love to clean a stall, I like to clean my house. I like work. I hate sitting.

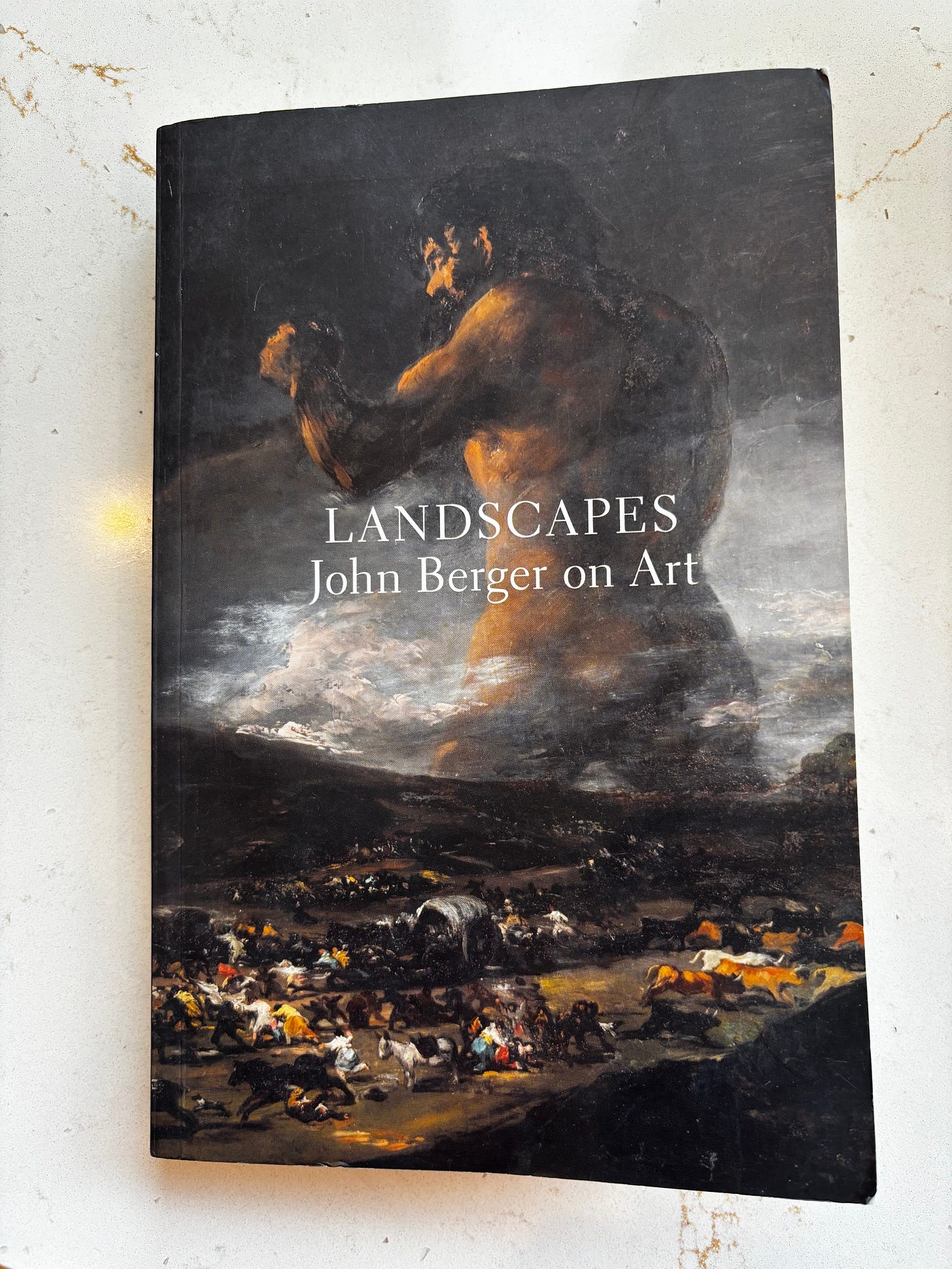

Speaking of doing, it was exactly a year ago that I first read John Berger’s Landscapes on Art. If you don’t know Berger, he’s worth reading. Especially if you like a crabby English Marxist who is an artist, essayist, art critic, and novelist. I sure do. In fact, I can’t get enough of crabby these days.

In The Storyteller, Berger writes about a local farmer, for whom Berger works occasionally. Their connection interests him; Berger is an intellectual, not a farmer, so what he asks, is their value to each other? It’s this: after work, they drink coffee and swap stories, both “historians of our time”.

I was stopped by this paragraph:

“The function of these stories, which are, in fact, close, oral, daily history, is to allow the whole village to define itself. The life of a village as distinct from its physical and geographical attributes, is the sum of all the social and personal relationships existing with it, plus the social and economic relations—usually oppressive—which link the village to the rest of the world. But one could say something similar about the life of some large town. Even of some cities. What distinguishes the life of a village is that it is also a living portrait of itself: a communal portrait, in that everybody is portrayed and everybody portrays; and this is only possible if everybody knows everybody.…A village’s portrait of itself is constructed, not out of stone, but out of words, spoken and remembered: out of opinions, stories, eyewitness reports, legends, comments and hearsay. And it is a continuous portrait, work on it never stops.”

Someone said to me the other day that it takes hours to run errands in our town (pop. 1500) because you have to stop and talk to everyone. It’s true. When I lived in cities, surprise and possibility popped up all the time, but the net effect was that they created my individual, personal experience of a place. The notion of a collective is easier to see in a small place, where our lives are intertwined even if we don’t know each other, and much of it is through work: we shop downtown at the hardware store or market, or get our tires rotated, and buy the neighbor’s eggs or hay, or swap irrigating chores for fruit tree pruning. Our value to each other, which is wholly separate from our affection—or lack of it—for each other, is clear. Our connections are indisputable.

Are you Berger-curious? Start with his 1972 book, Ways of Seeing, which explores how we see art, and also, the ways that advertising (and so, capitalism), have impacted the way we see…everything.

Three:

A story:

One of my neighbors was widowed a few years ago. His wife had pet llamas. When she died, the story goes, he became angry and released the llamas into the wild. Now, according to the story, there is a pack of five or six feral llamas roaming the draw that cuts through the mesa.

Ridiculous, I thought, when I heard the story. They’d have been killed by mountain lions or starved. Just on our farm, we’ve had three lion kills in the last year and a half, high circling birds alerting our dogs to the presence of flesh and bone and a bloody little snack left in our hayfields. Then, a month or so ago, when I was walking our dogs along a dirt road, I saw a llama in the distance. I knew it was a llama because of the puffy hair-do on top. The llama and I looked at each other. I grabbed my phone.

Just then, a guy whose house sits along the top of the draw came outside. “That a wild llama?” I yelled.

“Yeah,” he said. “Comes around bothering my horses.” He ambled down the road. We chatted a bit. He knew where I lived because his neighbor told him about my husband who’d looked at the neighbor’s apple trees. From there, we talked about the holidays, what we were making for dinner, our dogs. And then we were done. We shook hands. A bit of texture to the portrait.

Now, I see the llamas all the time. Turns out, you just have to know where to look, and there they are, skinny-necked, wary, watchy animals, spooking around the draw. Amid the cottonwoods, Siberian elms, and sagebrush, they shelter and other times, wander in search of whatever it is llamas want. They can get water from the irrigation ditches. A woman confessed to me that when she feeds her horses, she tosses a bit of hay out for the llamas. I wonder how far down the road can I go and still count someone as neighbor?

Spot the wild llama.

Four:

We are in a time of radical, thoughtless, venal leadership. As I write, in February 2025, The Associated Press has filed suit against the White House press officers and chief of staff for their punitive access ban of AP because AP continues to use the term “Gulf of Mexico” instead of Gulf of America. The AP suit suit opens this way:

“The White House has ordered The Associated Press to use certain words in its coverage or else face an indefinite denial of access.

The press and all people in the have the right to choose their own words and not be retaliated against by the government. The Constitution does not allow the government to control speech. Allowing such government control and retaliation to stand is a threat to every American’s freedom.

The AP therefore brings this action to vindicate its rights to the editorial independence guaranteed by the United States Constitution and to prevent the Executive Branch from coercing journalists to report the news using only government-approved language.”

Authoritarian forms of leadership at any level, political or parental, are meant to paralyze us, to keep us from doing, from the freedom of saying, of naming. From finding our own language. We read Orwell’s Animal Farm in high school and left class chanting, “Four legs good, two legs bad”, secure in the knowledge that we were reading about another time and place, that no such manipulation would ever happen here. But now it’s here, in the time of alternative facts, or what we used to call, before our post-ethics era, lies.

I struggle to write.

Five:

I am at my desk, which faces a window. Just beyond the window is our goat pasture, with four goats given to us by a local dairy as these goats either struggled to have an easy time being bred and delivering or are now too old to breed. (One of our daughters-in-law calls them “Hot Flash Ranch.”) One of them, Heather, just started on arthritis meds this week, and boy, is she springy.

Over the years there have been so many desks, so many pages. So many classrooms and writing students. To construct a story or essay is to impose a kind of order on language and events. Once, I knew how to do that and loved the hours at my desk.

But what used to be deeply engaging, even fun, now gives me pause. Who cares, really? (Also, see Sitting, hate it! above). I began writing at age ten, in a child’s attempt to have agency, to see story in the world. If you can create your own reality and get published by good publications, and so, get buy-in from other people about this reality you’ve created, I recommend it. But I often ask myself, Self, do you want to be at your desk, writing about life, or would you rather be out in it? Increasingly, the answer is out.

Some days, I open the barn doors and set my paints out on the workbench and spend hours there, brush to paper. Or hop in the truck with the dogs and a camera. To become wordless, in the middle of my life, to question the value of the narratives I can create, is both loss and opportunity. The loss, perhaps, is obvious: I first published work in a major newspaper at eighteen and my last publication was a few years ago. I have a lifetime of telling stories and exploring ideas. But it’s also true that to trace line and shape, to weave color and composition, is a way of being in the world with a new perspective, and that, in my fifties, is nothing to sneeze at.

Now, what I am supposed to do, according to Substack culture, is make a brand promise. Here’s what you’ll get, I am expected to say. Send me fifty bucks. But the truth is that I really have no idea what you’ll get. Except irregular communication from a middle-aged woman on a high desert mesa about a mixed bag of things from books to farm animals, about trying to learn to see with the eye of an artist plus—plus!—writing about not writing. No doubt there will be some storytelling, shit-talking, gossip, cultural analysis, and complaining. Oh, and inside scoop on being a bookseller! The best part? The failure of my brand promise works to your economic advantage because a publication that’s writing about not writing can only be free.

Alternatively, we could go out for drinks, but I like to stay home and you won’t get the pictures.

There’s more to say, but for now, I’ll just say thanks for coming along for the ride.

This SubStack will be free for foreseeable future.

Loved this. Looking forward to sharing with my sons, who also love to write, and also struggle to sit. More llama content, please.

Your last six weeks in five parts was a fun perspective. Of course the feral llamas was my fave...your survival too!